The origins of fabric structures

The origins of fabric structures can be traced back over 44,000 years to the ice age and the Siberian Steppe, where remains have been found of simple shelters constructed from animal skins draped between sticks. It is likely that structures of this type were the first dwellings actually constructed by humans, and it has even been suggested that simple textiles were used for spatial division and shelter before they were used as clothing.

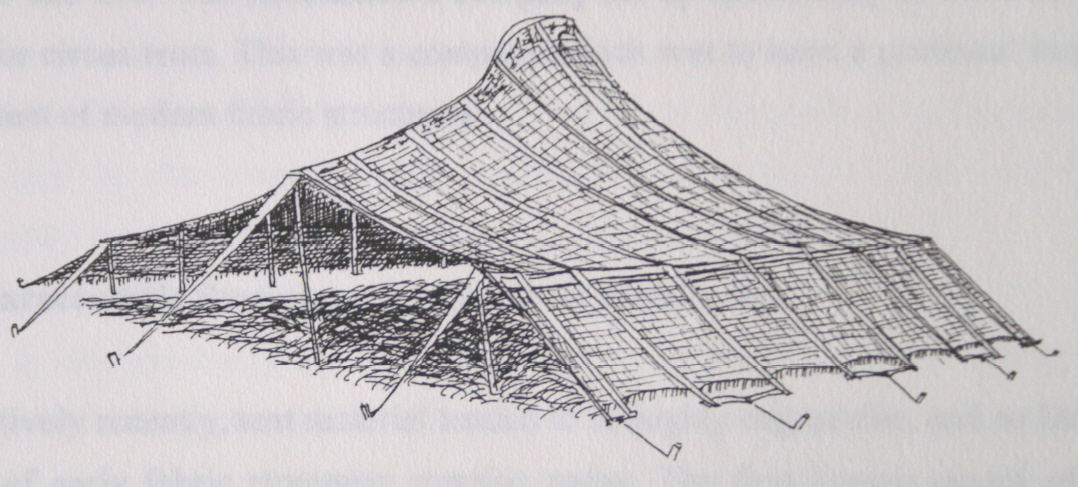

Initially associated with nomadic peoples, one of the earliest and most successful types of fabric structure was the loosely woven black tent. The black tent spread throughout the civilised world during the Arab conquests of the eighth century, and its descendants are still in use today.

Black tent.

From these nomadic origins, more permanent urban shading systems evolved. These were initially used to provide cover over streets and domestic courtyards, but later, larger 'velum' or 'velarium' were developed, primarily to provide shelter at theatres. In more recent times, simple cable stayed, prestressed fabric structures were used to provide decorative shelter for special events. These 'toldos' or 'envelet' were particularly popular at the end of the nineteenth century in the Cataluna region of Spain.

The lightweight portability of fabric structures inevitably brought about a long and close association with the military which began with the first major confrontations and has continued to the present day. By the first century BC the leather tents of the Roman Legions were commonplace, and the later Byzantine armies of the seventh century were recognised specifically by their simple tented shelters.

Godfrey Rhodes, an English Army Captain designed the standard tented field hospital (1858), however both this, and the subsequent British War Office, 'Handbook of Tentage', (1946) only served to illustrate the total lack of innovation in military tent design over the preceding thousand years.

During the twelfth century, elegant royal tents became fashionable in Western Europe. These 'novelty' structures grew progressively larger and more ornate during the sixteenth century, becoming symbols of frivolity and wealth at special events and tournaments. Their appearance however was more architectural than 'tented', with vertical walls and steeply pitched roofs. The famous 'Field of the Cloth of Gold' meetings between Francis I and Henry VII in 1520 were gloriously symptomatic of this trend.

In 1770 the first known circus tent, a large linen structure, was erected at Westminster Bridge. Travelling circuses began performing in 'nomadic' big tops around Europe around 1830, and by 1867 the first American railway circus had begun touring.

These early travelling circuses occupied roughly conical shaped 'big tops' which could be up to 50m in diameter. Such large enclosures required careful design and regular replacement because of the highly degradable nature of available materials. In 1872 Stromeyer and C.o. was established, a company set up specifically to satisfy the demand for circus tents. This was a company which was to have a profound impact on the development of modern fabric structures.

Characteristic features of early fabric structures.

Until relatively recently, tent material tended to be highly degradable, and so little physical evidence of early fabric structures remains today. The first known record of the actual appearance of primitive tents dates from the first century AD when early Persian kibitkas were depicted in a wall painting at a grave in Kerch.

It is known however that fabric structures developed and thrived predominately in regions where materials were scarce, or where survival required mobility; both conditions which tend to be brought about by low rainfall. Changing climates brought about slow transition from tents to huts and vice versa, and it was from the resultant process of intermediate modification that an enormous range of composite dwellings evolved. Many of these basic generic forms of structureare still used in remarkably unevolved forms throughout the world today.

The evolution of tents themselves can be categorised into urban and nomadic forms, however the essential characteristics of both types were similar. Their purpose was like that of clothing; that is to provide privacy, environmental modification and protection, intended as a means of generating shelter when necessary rather than as enclosures of permanent space.

From these purely functional origins however, the tent evolved over a period of many centuries to become a symbol of frivolity. Their temporary and degradable nature led to the inevitable emergence of style, as re-erection necessitated maintenance which required creation and so allowed personalisation. In architectural terms, their application eventually became monumental, providing a resource for which there was no fundamental need, and indeed historically many permanent monuments were preceded by temporary fabric structures. More recently, particularly in the West, fabric structures became almost entirely recreational, and other than for military purposes were used in ways which ran entirely contrary to their functional origins.

The development of modern fabric structures.

The simple dwellings described in the previous section tended to be fabricated in traditional ways by the intended occupants. As they degraded, their components were replaced, and so the overall design evolved. More complex fabric structures were predominately the craftsman's trade and not the domain of the architect. This was to change during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as architects became inspired by technological breakthroughs in structural engineering, made more appealing by architectural theorising on the emerging functional aesthetic.

In 1823 at around the same time that strong ropes first became commercially available, Claude Navier published a seminal study on suspension structures. The teething problems of the resulting generation of long-span structures were substantially laid to rest in 1838 when J.M. Rendel identified torsional stability as the major cause of bridge collapse. Large suspension structures rapidly became a common feature of engineering design, and it was not long before their spanning potential was used for large buildings.

At the 1896 Nizny Novgorod exhibition in Russia, the Structural Engineering Pavilion designed by V.G. Shookhov consisted of a large radial steel cable net pre-tensioned in both directions and clad with steel panels. It was believed that a similar structure composed of thicker 3mm steel sheets could span over 300m. This provoked an interest in the spanning potential of tension stabilised surfaces which has continued to the present day.

A parallel development began in 1918 when F.W. Lanchester patented a design for an 'air tent' in which it was proposed that a patterned balloon fabric could be inflated at a low pressure to form a habitable enclosure. In 1938 Lanchester developed the concept further with a design for an air supported dome spanning over 650m. Such air supported and air inflated structures had many potential applications but in 1946 a mass market was identified, creating 'radomes', minimal structure shelters which provided climatic protection for radar dishes.

Following successful trials between 1946 and 1950, the radome concept was applied to the DEW line early warning system, and in 1953 Walter Bird established the company Birdair primarily for the manufacture of radomes. Since 1946 tens of thousands of radomes have been manufactured, some of the largest being more than 60m in diameter. This generated a great deal of interest in the whole subject of tensile surface structures and stimulated intensive research into fabric composition. Fabric structures had become big business.

In the same year that Birdair began trading, the L.S. Dorton Arena in Raleigh was completed. Designed by Matthew Norwicki and Fred Severud, it was the first modern, doubly curved, pre-stressed saddle structure. Whilst itself not actually made of fabric, its completion is popularly believed to signify the birth of the modern 'tent'. The Raleigh Arena influenced many architects, and directly inspired both Saarinen's Yale Hockey Rink (1956) and Tange's two stadia for the Tokyo Olympics (1961).

A young German architect with a personal interest in lightweight and tension structures visited America during this period, where he met both Saarinen and Severud. The architect, Frei Otto, began exhaustive investigations into the structural principles behind this new generation of buildings. Even before the publication of his thesis 'Das Hangende Dach' in 1954, the practical implications of his work were brought to the attention of the tent manufacturer Stromeyer and Co. Peter Stromeyer made both his experience and resources available to Otto, and between them over the next twenty years, they were to undertake much of the intensive research and experimental construction which served to bring pre-stressed fabric structures into the vocabulary of the contemporary architect.

In 1957 Frei Otto established the Development Centre for Lightweight Construction using money he had received for commissions, and in 1964 re-named the Institute for Lightweight Structures it became affiliated to the University of Stuttgart. The Institute was primarily concerned with developing methods for deriving the ideal forms for tensile surfaces. Initially these investigations were based on detailed studies of soap films and wire mesh models, however later Otto was to meet the mathematician Fritz Leonhardt, who set about making this form finding process more mathematically explicit.

The variety of Otto's designs was wide. The first fabric structures he had built were a series of small music pavilions at the Federal Garden Exhibition at Kassel (1955), which were followed in 1957 by the similar twin saddle structures at the entrance to the Cologne Federal Garden Exhibition. He also designed convertible structures in the tradition of the Roman velarium, his first being the Theatre Terrace at Casino (1965).

Much of Otto's early research was embodied in the Montreal German Pavilion (1967), and a new permanence was heralded by the plexi glass clad cable net of the Munich Olympic Stadium (1969/70).

In the late 70's the world recession depressed the market for air houses, and this was compounded by a series of severe storms which resulted in a number of highly publicised deflations. Fabric structures in general, and airhouses in particular, were considered contrary to the new 'long life / low energy' construction ethic that was being advocated. This hindered the development of fabric structures, especially in Europe, and in 1974 Stromeyer's company went into receivership.

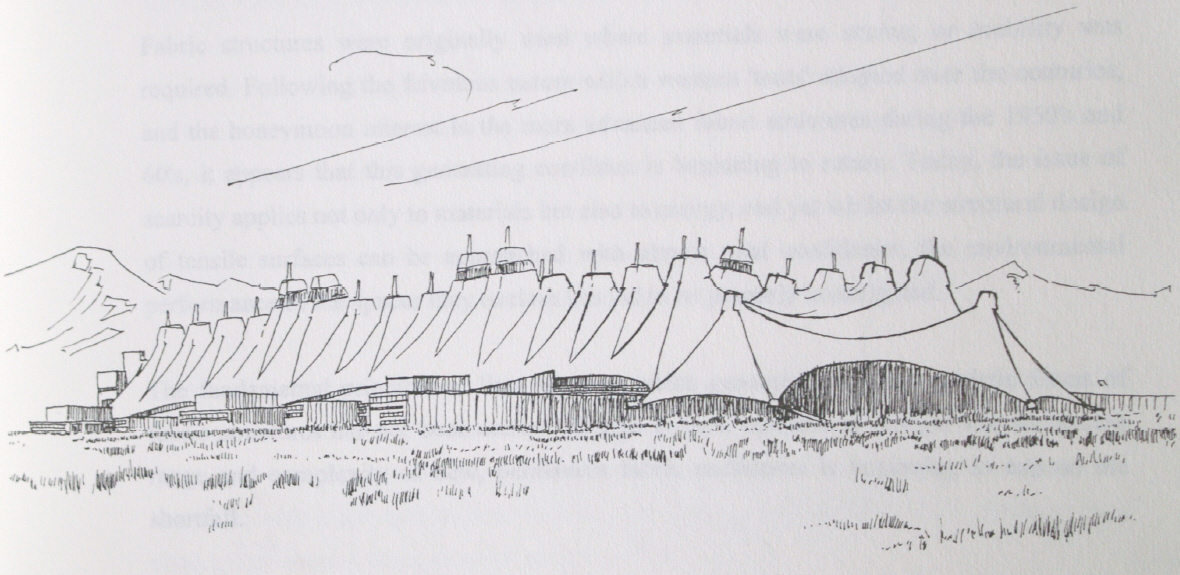

During the nineteen eighties and nineties, the fabric structures industry became more tentative, concerned with a confidence building process involving the consolidation of structural design techniques and the development of more reliable fabrics. This however provided a sound base from which the size and complexity of fabric structures increased, to give us the extraordinary developments we now associate with modern fabric structures such as the fabric roof of the Hajj Terminal at Jeddah Airport (1981) covering nearly half a million square meters, the 320m diameter Millennium Dome (2000) and Denver International Airport (below).

Denver International Airport.

[Millennium Dome, London]

This article was created by --Gregor Harvie.

https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/The_history_of_fabric_structures

No comments:

Post a Comment